Mobile data consumption across Sub-Saharan Africa is set to quadruple by 2030, according to the latest GSMA Mobile Economy 2024 Report.

On the surface, this paints a bright picture: Africa racing toward greater connectivity, innovation, and digital prosperity, but a deeper look reveals an uncomfortable reality — without urgent action, the rapid growth in mobile data will deepen existing inequalities, leaving rural, marginalized communities even further behind.

The Untold Story Behind Africa’s Data Surge

The projection of a fourfold increase in mobile data traffic is, at face value, a testament to Africa’s mobile-first future. GSMA expects average mobile data use to rise from 1.9 GB per month in 2023 to 8.0 GB per user per month by 2030. However, this surge in consumption will not be equally distributed.

The same report highlights that 60% of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who live within mobile broadband coverage still do not use mobile internet. This is not a failure of infrastructure — it is a failure of inclusion. The mobile economy is expanding, but the benefits are increasingly concentrated among urban, affluent users. Unless addressed, the digital usage gap threatens to reinforce existing divides across income, gender, geography, and education — all key issues tied to SDG 1 (No Poverty), SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), SDG 5 (Gender Equality), and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Access and Affordability — Africa’s Deepest Digital Divide

Access alone does not guarantee participation. Many rural Africans technically live within a 4G coverage area, yet lack the means to connect meaningfully. A smartphone remains a luxury in many parts of the continent; according to the Alliance for Affordable Internet, the cost of a basic smartphone exceeds 70% of monthly income for the poorest 20%.

Even for those with devices, mobile data costs remain among the highest relative to income globally. Combined with low levels of digital literacy, especially among women and rural populations, these barriers prevent millions from taking full advantage of mobile internet services.

Thus, the infrastructure may be there, but for the majority of low-income Africans, the digital door remains firmly closed.

The Risk of a Two-Speed Digital Africa

The future unfolding is not a uniformly connected Africa — it is two Africas. One Africa, centered in major cities like Nairobi, Lagos, Johannesburg, and Accra, will experience a boom in mobile apps, fintech, AI, and 5G-driven services. Here, access to high-speed mobile internet will empower businesses, enhance education, and create new jobs.

The other Africa — largely rural, poorer, less educated — will be increasingly locked out of these opportunities. Without smartphones, without affordable data, and without digital literacy programs, hundreds of millions will continue to live offline in a hyper-connected world. The risk is the emergence of a “connectivity-driven elite,” further deepening inequalities.

If we continue to measure progress purely by towers built or GBs sold, we will mistake expansion for inclusion — and Africa’s development goals will be derailed.

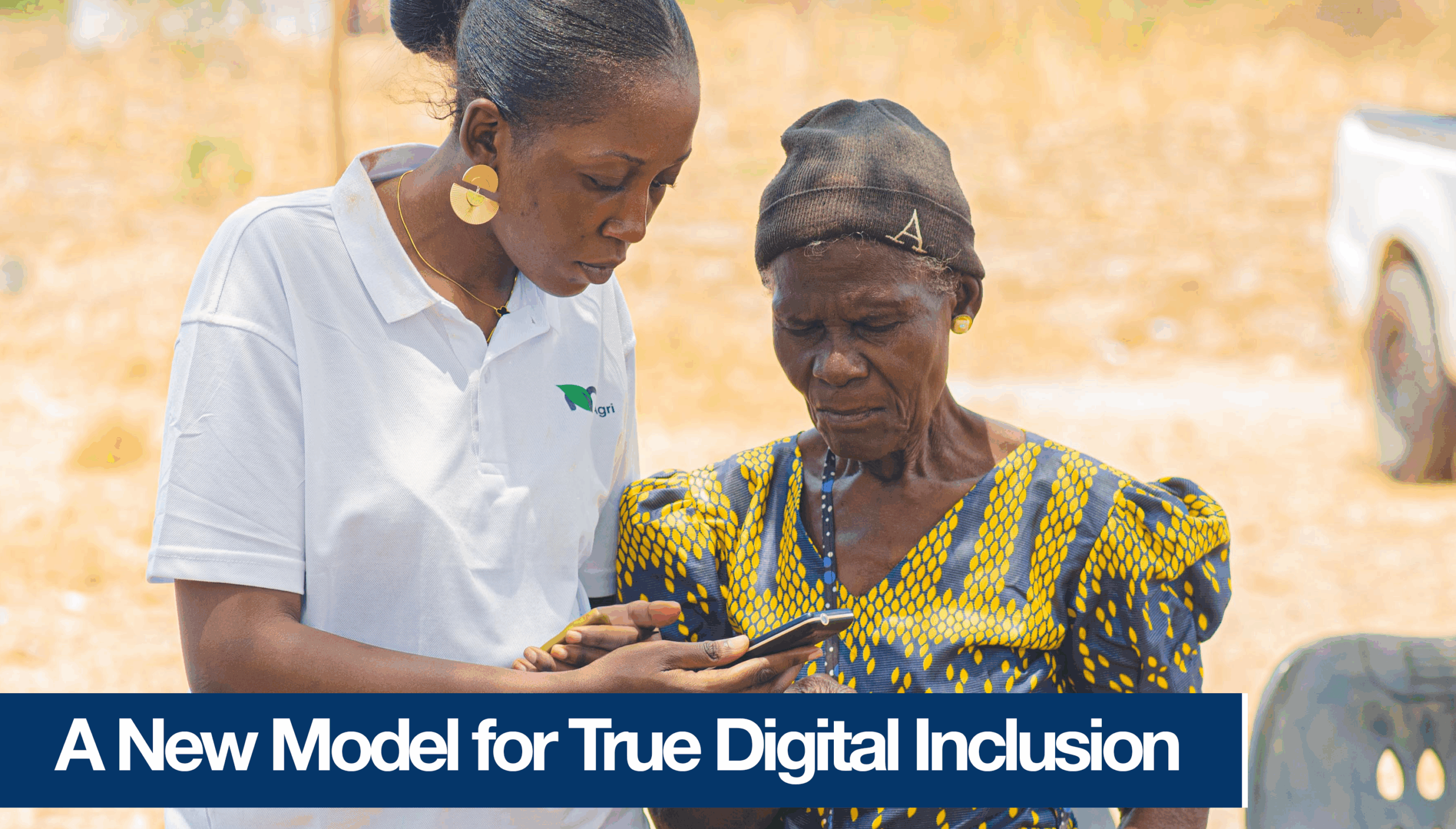

A New Model for True Digital Inclusion

Solving Africa’s digital divide demands more than expanding network coverage — it demands a complete reimagining of what true digital inclusion looks like.

First, affordability must move beyond device costs alone. The mobile industry and policymakers need to address the full cost of participation: device, data, skills, and services. Without interventions, the ITU projects that nearly 2.7 billion people globally will remain offline by 2030, and a significant portion of these will be in rural Africa.

Second, localized relevance will define success. If the digital economy is built only for urban, English-speaking, literate users, it will never scale inclusively. Content and services must be available in local languages, be culturally appropriate, and solve immediate, practical needs — from accessing market prices to learning new agricultural techniques or managing healthcare information. The GSMA Inclusive Tech Lab predicts that hyperlocal services will become the most important driver of first-time internet use in rural areas over the next decade.

Third, digital literacy must be treated as a core pillar of development, not an afterthought. Scaling affordable and culturally-sensitive digital literacy programs is as essential as building roads, clinics, and schools. Moreover, new models must blend low-tech and high-tech innovations. While 5G and fiber networks grab headlines, USSD, SMS, radio, and community Wi-Fi still have an irreplaceable role in reaching marginalized populations. These “last mile first” technologies will remain vital well into the 2030s if Africa aims to close not just the coverage gap, but the usage gap.

Finally, partnerships will determine impact. No single company, government, or NGO can solve the digital divide alone. New coalitions must emerge — bringing together mobile operators, innovators, donors, governments, and communities — to build scalable, sustainable models that ensure no one is left behind.

Connectivity that excludes the poor is not development; it is displacement. If we are to truly align with SDG 1, 2, 5, and 10, innovation must meet people where they are — not where we wish them to be.

Data Alone Will Not Deliver Development

The projected surge in Africa’s mobile data consumption is a double-edged sword. It offers enormous potential for economic growth, education, healthcare, and empowerment — but only if the benefits are distributed equitably. If we fail to address the affordability gap, the skills divide, and the lack of relevant services, the data boom could leave the most vulnerable even more isolated from opportunity.

Africa’s digital future must be built not just for those who already have access — but for the millions who are still waiting for their first real connection.

Real progress will be measured not by the GBs consumed, but by the lives transformed.